25. Bundeskongress für Schulpsychologie

Short Portrait

(Deutsch) Fachtagung Psychologiedidaktik und Evaluation 2024 in Mainz

Sorry, this entry is only available in Deutsch.

International Conference on Motivation & Emotion 2024 will be held at University of Bern 28. – 30. 8. 2024

The 18th International Conference on Motivation & Emotion 2024 will be held at Unversity of Bern, Switzerland. The chair will be Tina Hascher.

The main theme “Motivation & Emotion: Resources and challenges for teaching, learning, and research” provides a wide umbrella also to the practical aspects of motivational & emotional research.

The 18th International Conference on Motivation & Emotion 2024 will be held from 28. to 30. 8. 2024, preceded by the Summer School from 26. to 27. August 2024.

18th International Conference on Motivation 2024 (SIG 8): 28. – 30. August 2024

Summer School 2024: 26. – 27. August 2024

Location: University of Bern

Organizers: Prof. Dr. Tina Hascher, Dr. phil Dr. phil. Julia Mori, Tatijana Lovrinovic, Kristina Kelava

Deadline for proposal submission: 29. February 2024 (Call, PDF, 83KB)

Deadline for earli bird registration: 31. May 2024

Deadline for registration: 2. August 2024

Programm Overview: https://icm2024.unibe.ch/program/program_overview/index_eng.html

Website: https://icm2024.unibe.ch/index_eng.html

(Deutsch) Was ist wirksamer Unterricht?

Sorry, this entry is only available in Deutsch.

Motivation to Study: 24 Tips for Teachers

Motivation to Study: 24 Tips for Higher Education

The students in your lectures and seminars maybe bored, lethargic or have no motivation following your teaching? Do you experience this sometimes?

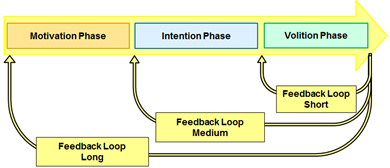

You will find 24 tips for reflecting your academic teaching. These tips are derived from my recent research projects and grounded on the Integrated Model of Learning and Action (ILMA).

Academic Motivation: The Start (IMLA: Motivation Phase)

In the beginning, students need to realize what to expect. You can initialize the learning internalization process by providing in-depth information about the learning topic. The students can then establish a first learning orientation for themselves. They should become aware about their own strengths and weaknesses. The main emphasis should be on the learning process (and not the learning content). Teaching should always promote self-development and self-transformation. Other prerequisites for encouraging academic motivation are free choices, such as selecting a learning topic. This promotes the perceived autonomy and subsequently increases the acceptance of responsibility. This is the starting point for an increased motivation for learning.

,

The Learning Intention (ILMA)

Each student learns best in a specific way. And this way maybe very different from the teacher’s learning approach. Support your students in finding new learning methods and learning strategies. Encourage them actively to explore, experience and evaluate new learning methods.

,

The Implementation of Learning Actions (IMLA: Volition Phase)

The implementation of the learning process can be very different for each student. Create safe learning spaces which can be used for individual learning processes.

,

Motivation over Time: Feedback Loops (IMLA)

In order to keep the learning processes motivated and effective over time students should regularly reflect on their learning progress and their self-transformation. Therefore, provide your students with feedback on their individual learning progress.

.

This work is licensed uner Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International

Image by wagrati_photo from Pixabay

Motivated Learning

Motivated learning

First of all, one might wonder if motivated learning is necessary at all. Is is not possible to learn without motivation? At least as far as short-term learning success is concerned, this question must be answered positively: it is possible to successfully learn without motivation. However, the empirical results from our “Zeitlast” (workload) studies also show that such a learning outcome without motivation is usually accompanied by a greater perceived effort and a higher objective time requirement. It may also be assumed that the acquired knowledge content is less accessible – in particular, that the transfer to new situations is disrupted resulting in some inertia of the knowledge thus acquired.

Conversely, it can be inferred that motivated learning requires less personal effort, is more time-effective and the resulting knowledge is more universally applicable.

These advantages of motivated learning are directly related to the fact that intrinsic motivation is linked to the self-system “extension memory” already described in the blogpost 1 “Descartes’ Error“. The right hemispheric extension memory accompanies and enables the internalization processes necessary to perform a learning task with intrinsic motivation.

Here, the extension memory has a threefold function:

- It allows feeling the fit between learning tasks and the learner and thus creating a first internalization of the learning task. Subsequently, an ascription of responsibility for the learning task can be developed.

- The extension memory also accompanies the experience of self-efficacy. In particular, whether a particular learning method or learning strategy really suits you.

- In the actual performing of the learning action, the extension memory will assess whether I continue to feel comfortable with the concrete learning processes.

The activation of the extension memory in the learning process is thus the prerequisite for a holistic association of the self with all phases of the learning process. A large correspondence between the self and the learning regulation will trigger the effects of an intrinsic motivation:

- Learning is easy and time flies by (flow experience).

- Through a high degree of associations with the self-system many methods can be associated that can be used flexibly during the learning process.

- A close connection with the self-system also enables a better self-motivation, which allows a constructive handling of setbacks and, if necessary, guarantees a longer study of the subject matter.

- Finally, strong associations of the acquired knowledge with the self-system result in a more flexible retrieval of the knowledge content in different situations and thus promotes a high retention performance.

The next blog post will explain how a learning environment can be designed in such a way that the highest possible intrinsic motivation for learning can emerge (motivated design).

.

This work is licensed uner Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International

(Deutsch) Was könnte gelingende Wissenschaftskommunikation sein?

Sorry, this entry is only available in Deutsch.

(Deutsch) Wie kann ich mit meiner Angst konstruktiv umgehen?

Sorry, this entry is only available in Deutsch.

(Deutsch) Rezension zu Walter Isaacson The Code Breaker

Sorry, this entry is only available in Deutsch.

(Deutsch) Schulische Bildung in Zeiten von Corona

Systematic Reviews in Educational Research – Free Download

Systematic Reviews in Educational Research – an Open Acess Handbook

This new and Open Access Handbook of Systematic Reviews in Educational Research covers different aspects of a systematic review: methodical considerations, reflections as well as practical examples and applications. For example in Chapter 2 section 4 a reflection on Transparent Methodological Assessment of Studies is provided.

This book is edited by Olaf Zawacki-Richter, Michael Kerres, Svenja Bedenlier, Melissa Bond and Katja Buntins.

The full book can be downloaded from Springer for free as PDF or as EPUB.

All chapters can also be dowonloaded separately as PDF here.

Target Groups Researchers, instructors, and students in the field of education and related disciplines

ISBN: Print ISBN 978-3-658-27601-0 Online ISBN 978-3-658-27602-7

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-27602-7

Licence: CC BY

Thinking in the Universe?

Thinking in the Universe – Are there Intelligent Species in the Galaxy?

In his book “Brief Answers to the Big Questions” in chapter three, Stephen Hawking raised the question of whether there can be intelligent living beings in the universe. My answer would be “yes” – there must be intelligent and thinking beings in the universe. But first the question has to be answered what thought processes are needed for – in general.

Thinking becomes necessary living in a changing environment. Through calculating or holistic thinking processes, changes can be anticipated and the chance of survival of a species can systematically be increased. And it can also be assumed that most environments in the universe will change.

Even at the quantum level it can be seen that location and impulse cannot be determined simultaneously. This unpredictability is already hidden in the micro level and probably continues onto the macro level. Conversely, it can be concluded that the unpredictability of many worlds in the universe increases the chance for thinking living beings. On a galactic scale, there should therefore be a multitude of beings who gain an advantage by thinking.

This of course raises the question why we haven’t been visited by extraterrestrials long ago. Stephen Hawking himself gives a possible answer: probably, the aggressive species have usually destroyed themselves, while the peaceful ones have no interest in reaching or destroying other habitable planets.

Interview mit Julius Kuhl zur PSI-Theorie

Sorry, this entry is only available in Deutsch.

(Deutsch) Keine Lust auf Schule? Bestrafen oder Belohnen?

Sorry, this entry is only available in Deutsch.

(Deutsch) Rezension Trisolaris-Trilogie von Liu Cixin – Jenseits der Zeit (Band 3)

Sorry, this entry is only available in Deutsch.

(Deutsch) Studium und Studienwahl Pädagogische Psychologie

Sorry, this entry is only available in Deutsch.

Descartes’ Error – sentio, ergo sum

Let’s do a simple thought experiment: when I think of violence, am I a criminal? When I think of giving presents to someone else, am I a benefactor?

Even in this simple thought experiment, it becomes clear that conscious thinking can always focus on just one point – just as speaking does. Does this one focus defines human being? Hardly likely.

What constitutes humanity much more is the sum of the experiences of a human being. This wealth of experiences could therefore be considered as being human.

The exciting question is now how we draw on this wealth of experience. Certainly, we can consciously remember a single event in our past. However, does that help us to recognize who we are?

There is one system that is able to assess the vast majority of personal experiences at once. Personality psychologist Julius Kuhl calls this system “extension memory”. This system can assess a person’s wealth of experience in a parallel and holistic way and gives a feeling as a result of this assessment.

This self-system or so-called extension memory becomes especially important when it comes to assessing and evaluating social interaction in a matter of seconds. For example, when I meet a person I did not know before, after a very short time I know how to judge that person.

Maybe this first assessment is not very accurate. But at least it gives an indication of how I should deal with this person in the future. Thus, the extension memory is capable of retrieving all associations with a new person within a very short period of time and of pooling those associations in a feeling for that person. Therefore, if everything goes well, within a few moments I know if I can trust this person. Or if I’d rather avoid this new person.

The extension memory is also responsible for a whole series of processes, such as the intrinsic motivation for learning, which we just demonstrated in the current research project Sensomot – read this in the next blog post “motivated learning“.

So we can say with certainty that Descartes was wrong. This sentence might be much more accurate:

“Sentio, ergo sum.” (I feel, therefore I am)

This work is licensed uner Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International

(Deutsch) Schulnoten oder Rohrstock – Warum sind Schulnoten so verführerisch und so gefährlich?

Sorry, this entry is only available in Deutsch.

(Deutsch) Kleine Daten für das Lernen – Small Data in Learning

Sorry, this entry is only available in Deutsch.

(Deutsch) Notengebung und selbstreguliertes Lernen oder die Rückkehr des Odysseus

Sorry, this entry is only available in Deutsch.

(Deutsch) Digitalisierung in der Bildung – Was ist wünschenswert, was ist machbar?

Sorry, this entry is only available in Deutsch.

(Deutsch) Vorsätze oder Wirf-Deine-Neujahrsvorsätze-über-Bord-Tag am 17. Januar

Sorry, this entry is only available in Deutsch.

(Deutsch) Langeweile

Sorry, this entry is only available in Deutsch.

It is Creeping Back … Learning Outcomes Often Follow Behaviourist Tradtion

The Concept of Learning Outcomes Often Follows Behaviourist Tradtion

Learning outcomes as a concept has encountered a revival since the beginning of the Bologna process in 1999. The concept itself has a longer history with its roots in the behaviourist tradition of the 1960s. The goal of this review is to study how the historical roots of learning outcomes are noted in current research articles since the launch of the Bologna process and whether the concept of learning outcomes is used critically or uncritically. The review of 90 articles shows that the behaviourist tradition is still evident in the 21st century research with 29% of the articles directly and 11% indirectly referring uncritically to the respective publications or to the behaviourist epistemology.

Citation: Murtonen, M., Gruber, H., & Lehtinen, E. (2017). The return of behaviourist epistemology: A review of learning outcomes studies. Educational Research Review, 22(Supplement C), 114-128.

Find the full article here: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2017.08.001

Find more interesting articles here.

Conditioning factors of test‑taking engagement in PIAAC

Conditioning factors of test‑taking engagement in PIAAC: an exploratory IRT modelling approach considering person and item characteristics

Background

A potential problem of low-stakes large-scale assessments such as the Programme for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies (PIAAC) is low test-taking engagement. The present study pursued two goals in order to better understand conditioning factors of test-taking disengagement: First, a model-based

approach was used to investigate whether item indicators of disengagement consti-tute a continuous latent person variable by domain. Second, the effects of person and item characteristics were jointly tested using explanatory item response models.

Methods

Analyses were based on the Canadian sample of Round 1 of the PIAAC, with N= 26,683 participants completing test items in the domains of literacy, numeracy, and problem solving. Binary item disengagement indicators were created by means of item response time thresholds.

Results

The results showed that disengagement indicators define a latent dimension by domain. Disengagement increased with lower educational attainment, lower

cognitive skills, and when the test language was not the participant’s native language. Gender did not exert any effect on disengagement, while age had a positive effect for problem solving only. An item’s location in the second of two assessment modules was positively related to disengagement, as was item difficulty. The latter effect was negatively moderated by cognitive skill, suggesting that poor test-takers are especially likely to disengage with more difficult items.

Conclusions:

The negative effect of cognitive skill, the positive effect of item difficulty, and their negative interaction effect support the assumption that disengagement is

the outcome of individual expectations about success (informed disengagement).

Full Article:

Goldhammer, F., Martens, T. & Luedtke, O. (2017). Conditioning factors of test-taking engagement in PIAAC: an exploratory IRT modelling approach considering person and item characteristics. Large-scale Assessments in Education, 5, 18. DOI: 10.1186/s40536-017-0051-9 [html, pdf]

Please find other publications here.

New Book on PSI Theory: Why People Do the Things They Do – Building on Julius Kuhl’s Contributions to the Psychology of Motivation and Volition

Buildung on the central contributions of Julius Kuhl like the PSI Theory leading researchers including Charles S. Carver and Richard M. Ryan reflect the implications for their own work.

This book is edited by Nicola Baumann, Miguel Kazén, Markus Quirin & Sander L. Koole

The first chapter can be dowloaded here.

The book ISBN: 9780889375406 can be bought here.

Citation: Baumann, N., Kazén, M., Quirin, M., & Koole, S. L. (Eds.). (2018). Why People Do the Things They Do. Göttingen: Hogrefe.

Please find the table of content here.

(Deutsch) Vortrag über Motivation, Selbstregulation und Potenzialentfaltung auf dem Netzwerktreffen Hochbegabung

Sorry, this entry is only available in Deutsch.

RSS feeds motivation research, learning research, higher education and learning with computers

Please find some RSS feeds from important journals in the field of motivation, learning, higher education and computer here.

Please find some RSS feeds from important journals in the field of motivation, learning, higher education and computer here.

Picture by Nicole Henning CC 2.0

Workshop: Fostering Learning at University

Thomas Martens conducted a workshop on 30 June 2016 at the TU Dresden with the title “Fostering Learning at University: the Heterogeneity of Motivational Processes”. This workshop showed different ways of learning motivation and how the individual learning processes of students can be promoted.

Thomas Martens conducted a workshop on 30 June 2016 at the TU Dresden with the title “Fostering Learning at University: the Heterogeneity of Motivational Processes”. This workshop showed different ways of learning motivation and how the individual learning processes of students can be promoted.

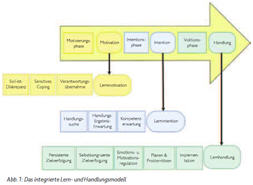

As theoretical basis served the Integrated Model of Learning and Action (IMLA) which divides the typical processes of learning in three main phases (motivation, intention and volition phase) and defines the relationship to the findings in neuro science from Julius Kuhl (2000).

Photo: kanenas.net

Motivation and Educational Perspectives of Gifted Children

At the conference of “Bildung und Begabung” [Education & Giftedness] 31 May 2016 with the title “Perspektive Begabung: Diversität als Chance” [Future of Giftedness: Diversity as an Opportunity] Thomas Martens delivered a keynote entitled “Motivation and Educational Perspectives of Gifted Children”.

At the conference of “Bildung und Begabung” [Education & Giftedness] 31 May 2016 with the title “Perspektive Begabung: Diversität als Chance” [Future of Giftedness: Diversity as an Opportunity] Thomas Martens delivered a keynote entitled “Motivation and Educational Perspectives of Gifted Children”.

While one child follows his interests and develops remarkable skills herein, the other child seems rather lackluster and disinterested. Researcher have long been agreed that motivation is a driving factor when giftedness is translated into performance. As different as young people are so different are their motivation profiles. Family, friends, and teachers – they all influence the development of motivation. This can be promoted by empathetic caregivers or be attenuated in critical phases of life. How can we, in the face of these different conditions, support children and young people developing motivation and regulating them properly? How can school or other learning environments handle these motivation processes? What help can be offered?

A podcast of this talk is online (german only):

Different Transitions towards Learning at University: Exploring the Heterogeneity of Motivational Processes

This chapter discusses transitions towards learning at university from a perspective of regulation processes. The Integrated Model of Learning and Action is used to identity different patterns of motivational regulation amongst first-year students at university by using mixed distribution models. Five subpopulations of motivational regulation could be identified: students with self-determined, pragmatic, strategic, negative and anxious learning motivation. Findings about these patterns can be used to design didactic measures to support students’ learning processes.

This chapter discusses transitions towards learning at university from a perspective of regulation processes. The Integrated Model of Learning and Action is used to identity different patterns of motivational regulation amongst first-year students at university by using mixed distribution models. Five subpopulations of motivational regulation could be identified: students with self-determined, pragmatic, strategic, negative and anxious learning motivation. Findings about these patterns can be used to design didactic measures to support students’ learning processes.

Please find a preview of this chapter here.

Please cite this chapter as: Martens, T. & Metzger C. (in press). Different Transitions of Learning at University: Exploring the Heterogeneity of Motivational Processes. Erscheint in E. Kyndt, V. Donche, K. Trigwell & S. Lindblom-Ylänne (Eds.), Higher Education Transitions: Theory and Research. EARLI Book Series “New Perspecitves on Learning and Instruction”. London: Routledge.

(Deutsch) Lernerfolg im Studium

Sorry, this entry is only available in Deutsch.

Sensor Measures of Motivation for Adaptive Learning (SensoMot)

New research projekt started: Sensor Measures of Motivation for Adaptive Learning (SensoMot)

Motivation is one major factor for facilitating deep learning processes. The goal of the research project „SensoMot“ is to predict critical motivational conditions using sensor measures. By deriving adaptive mechanisms, the learning process can subsequently be tailored to the motivational needs of the learner (project description).

Motivationsprozesse im Jugend- und Erwachsenenalter [Motivation Processes in Adolescence and Adulthood]

This article examines conditions for a successful motivation for education and training: Why can many teenagers and young adults easily motivate themselves for schools and education, while other show serious motivational difficulties? On the base of identified motivational processes measures are suggested that educational institutions can provide.

This article examines conditions for a successful motivation for education and training: Why can many teenagers and young adults easily motivate themselves for schools and education, while other show serious motivational difficulties? On the base of identified motivational processes measures are suggested that educational institutions can provide.

[http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0111-pedocs-109762] [pdf]

(available in German language only – sorry!!!)